On Martin Heidegger’s The Origin of the Work of Art

“Is there to be no knowledge in art? Does not the experience of art contain a claim to truth which is certainly different from that of science, but just as certainly is not inferior to it? And is not the task of aesthetics precisely to ground the fact that the experience of art is a mode of knowledge of a unique kind, certainly different from that sensory knowledge which provides science with the ultimate data from which it constructs the knowledge of nature, and certainly different from all moral rational knowledge, and indeed from all conceptual knowledge — but still knowledge, i.e., conveying truth?”

— Hans-Georg Gadamer | Truth and Method

In this paper I will attempt to give a explicative summary of Martin Heidegger’s The Origin of the Work of Art. This essay is packed full of insights, so, for the sake of brevity, I will only be focusing on its main ideas. What probably stands out the most about this essay is the originality of Heidegger’s thinking concerning the origin of the work of art, i.e., the Being of the work of art. Heidegger doesn’t conceive of the work of art, or, I should say, a great work of art, in terms of representation or form and content. While aesthetics has long used these categories in order to analyze and explain artworks, Heidegger believes that they are unsuitable for investigating the Being of works of art. This, of course, is not to say that these categories are totally useless in relation to the study of works of art. Heidegger will lay out his own categories through which the Being of artworks is revealed. Surprisingly, Heidegger only sparsely mentions beauty in the course of his inquiry. Another surprise in this essay is that Heidegger, unlike many philosophers from Plato to Nietzsche, argues that truth and art are deeply interconnected — not mutually exclusive. Heidegger flat out rejects the belief that art is subjective, a belief that is very much in style to this day.

Conceptual and Terminological Introduction

Before we can begin our discussion of The Origin of the Work of Art some preparatory work is required. Heidegger’s thinking was a continuous process of philosophical inquiry; he famously said, “I have no philosophy at all” (History of the Concept of Time, pp. 301–2). In order to understand Heidegger’s later thinking, one must first have a general familiarity with his early thinking. Most importantly the thinking captured in his masterpiece Being and Time. However, there were two concepts that Heidegger focused on the most throughout his career and those are the ones we must focus on as well. These two concepts are Being and truth (unconcealment).

1. Being

Despite all of the twists and turns one finds in the development of Heidegger’s thinking, one thing remained the same, namely, the prioritization of Being. Throughout his entire career Heidegger primarily concerned himself with one question: What is the meaning of the word “Being”? He felt as though the philosophical tradition had forgotten this question, and that for philosophy to advance it must ask it anew. Heidegger never came to a final definition of “Being”, but that’s not to say that the word was used meaninglessly by him. To understand the provisional meaning of “Being” we must turn our attention to Heidegger’s Being and Time. In the first introduction of this book, while speaking in relation to the question of the meaning of “Being”, Heidegger says, “In the question which we are to work out, what is asked about is Being — that which determines entities as entities, that on the basis of which entities are already understood, however we may discuss them in detail” (Being and Time, pp. 25–6). Being is that by which beings are understood as beings. Being is the intelligibility of beings qua beings. Being is the vague and elusive background familiarity we have that enables us to skillfully deal with particular beings. This might sound strange at first, seeing how most people would consider the meaning of “Being” to be something along the lines of the totality of what is, i.e., reality. But Heidegger famously points out that “The Being of entities ‘is’ not itself an entity” (Being and Time, p. 26). The distinction between Being (das Sein) and beings/entities (das Seiende) would later be referred to by Heidegger as “the ontological difference”: “This difference has to do with the distinction between beings and being. The ontological difference says: A being is always characterized by a specific constitution of being. Such being is not itself a being” (The Basic Problems of Phenomenology, p. 78). Heidegger argued that philosophy (metaphysics) has always had two ontologically inappropriate tendencies: first, it tends to confuse and/or reduce Being to a being, he called this tendency “ontotheology”, and, second, philosophy has also had a tendency to conceive of beings in terms of presence, meaning that something is as long as it is present in some sense (this second tendency would come to be known as metaphysics of presence).

In Being and Time Heidegger is doing ontology: the study of Being. But how does one begin studying Being? Well, one must study Being by studying a being. But what being should one study? Heidegger said that one ought to study the being that has an understanding of Being — this being is Dasein. “Dasein” is simply Heidegger’s term for human beings; in German it means “being-there.” This means that before one can engage in general ontology, one must engage in fundamental ontology, that is, the ontology of the being that has an understanding of Being. Heidegger didn’t choose to call us Dasein arbitrarily; no, he felt as though the words most often used by philosophers to designate human beings, words like “consciousness”, “self-consciousness”, “subject”, “soul”, etc., carried far too much metaphysical baggage, and, thus, found it necessary to come up with a new term for human beings. But in calling us Dasein, Heidegger wasn’t simply renaming us — he was re-conceiving us. Philosophers, starting with René Descartes, had conceived of human beings as subjects (mental substances: isolated, self-subsistent, self-conscious minds that do not require any other minds or finite things in order to exist). For Descartes, a human being can exist without a world; he arrived at this position through skepticism. While he found it totally possible to doubt the existence of the external world, Descartes also found that he couldn’t doubt his own existence because to be deceived about the existence of the external world presupposes the existence of the person being deceived. The indubitability or apodicticity of the self-subsistent existence of the “I” (Cogito) is what Descartes “proves” in his statement: “I think therefore I am” (“Cogito ergo sum.”). Against this view of the self as a worldless subject, Heidegger phenomenologically established that Dasein is always Being-in-the-world. To be a self is to have a world. But that begs the question: What is a world?

Heidegger makes a distinction between two kinds of worlds: (1) the totality of actual things, (2) the totality of referential totalities. The first meaning of “world” is best thought of as the universe, i.e., the space-time continuum, this is the plane of substances. Descartes defined “substance” in his Principles of Philosophy like this: “By substance we can understand nothing other than a thing which exists in such a way as to depend on no other thing for its existence” (The Philosophical Writings of Descartes: Volume I, p. 210). A substance, for example, a rock, doesn’t require any other substance in order to exist. Substances are to be thought of in terms of presence, in that, they are either present in the universe, or present at the moment, or present before consciousness. Substances have their own mode of Being which Heidegger referred to as “presence-at-hand.” The second meaning of “world” is the more important one for Heidegger, but, to be able to understand it, we must first understand what a referential totality is. By “referential totality”, Heidegger means the web-like structure of equipment, that is to say, tools. Tools, unlike substances, are not self-subsistent, they rely on other beings for their Being. In Being the beings that they are, tools refer to other beings. It is important to note that Heidegger called the mode of Being of equipment “readiness-to-hand.” Let us consider Heidegger’s famous phenomenological description of equipment presented in Being and Time:

“We shall call those entities which we encounter in concern “equipment.” In our dealings we come across equipment for writing, sewing, working, transportation, measurement. . . . Taken strictly, there ‘is’ no such thing as an equipment. To the Being of any equipment there always belongs a totality of equipment, in which it can be this equipment that it is. Equipment is essentially ‘something in-order-to. . .’. A totality of equipment is constituted by various ways of the ‘in-order-to’. . . . In the ‘in-order-to’ as a structure there lies an assignment or reference of something to something. . . . Equipment — in accordance with its equipmentality — always is in terms of its belonging to other equipment: ink-stand, pen, paper, blotting pad, table, lamp, furniture, windows, doors, room. . . . What we encounter as closest to us (though not as something taken as a theme) is the room; and we encounter it not as something ‘between four walls’ in a geometrical spatial sense, but as equipment for residing. Out of this the ‘arrangement’ emerges, and it is in this that any ‘individual’ item of equipment shows itself. Before it does so, a totality of equipment has already been discovered. Equipment can genuinely show itself only in dealings cut to its own measure (hammering with a hammer, for example); but in such dealings an entity of this kind is not grasped thematically as an occurring Thing, nor is the equipment-structure known as such in the using. The hammering does not simply have knowledge about the hammer’s character as equipment, but it has appropriated this equipment in a way which could not possibly be more suitable. In dealings such as this, where something is put to use, our concern subordinates itself to the “in-order-to” which is constitutive for the equipment we are employing at the time; the less we just stare at the hammer-Thing, and the more we seize hold of it and use it, the more primordial does our relationship to it become, and the more unveiledly is it encountered as that which it is — as equipment. . . . The peculiarity of what is proximally ready-to-hand is that, in its readiness-to-hand, it must, as it were, withdraw in order to be ready-to-hand quite authentically.”

(Being and Time, pp. 97–9)

The main points of this passage that one should take notice of are the following: (1) a piece of equipment necessitates and presupposes other pieces of equipment (a referential totality of equipment) in order to be the piece of equipment that it is; (2) equipment is truly what it is only when it is being used transparently; (3) equipment, unlike substances, only shows itself as itself when it is withdrawn, i.e., not present. Equipment has a completely different ontological structure than substances have, whereas we conceive of the latter in terms of self-subsistence and presence, we must conceive of the former in terms of referentiality and withdrawnness.

We are now in a position to understand Heidegger’s second meaning of world: a world is the totality of all significant, referential totalities. A referential totality is its own little world within the world as a whole. We often speak of the world of a teacher, or an athlete, or a musician, and what we mean by this is the significant context of references in which that person abides, but each of these little worlds are only a part of the world at large: the totality of all referential totalities.

Now, let us return to Dasein for at moment. Heidegger goes on to establish that equipment not only refers to other equipment, but also to the goals, projects and plans of Dasein. Why does a person pick up a hammer? — In order to hammer nails. And why does a person hammer nails? — In order to fasten boards together. But doesn’t each in-order-to share a common purpose with the other ones? — Yes, of course, in this case it would be the purpose of building a house. And why do houses get built? — So people can have a place to live. Tools necessitate human projects to be what they are, and humans can only be the selves that they are through the use of equipment. Let’s take at look at a much more concrete example, the example being myself. I’m sitting in the chair I’m currently sitting in in order to type on my laptop; I also have my lamp turned on in order to have the appropriate lighting for looking at a computer screen; the lampshade is angled in such a way in order to not have too much light in my eyes; my thermostat is set at 72° in order to keep me from getting either too cold or too warm; Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue is playing in order to keep me motivated and enthusiastic; my copy of Being and Time is sitting close by on the table in order to allow me to type out quotes when needed; and all of this points towards me writing my explicative summary of The Origin of the Work of Art (Heidegger called this pointing towards the “towards which”). But it doesn’t end there. The purpose, or as Heidegger put it “for-the-sake-of-which”, I have in writing this summary is the possibility of getting a good grade, as well as preparing me for the work in philosophy I intend to accomplish. Getting good grades is a possibility of Dasein, but why would a Dasein desire good grades? For the ultimate sake of being the self he or she wants to be. Heidegger said that Daseins “comport themselves toward their own Being” (this was inspired by Søren Kierkegaard’s formulation of the self: “The self is a relation that relates itself to itself.”). But this analysis has led us to a circle (Heidegger calls this “hermeneutic circularity”). Equipment can only be what it is in relation to Dasein, but Dasein can only be a self in relation to worldly equipment. And with this circle, Heidegger has deconstructed the concept of the Cartesian self, i.e. the substantial, worldless self. Descartes set up a binary opposition between the self and the world, whereby he privileged the former term and devalued the latter. But Heidegger has revealed that the devalued concept is actually ontologically essential to the privileged one. Dasein always exists as Being-in-the-world: no world = no self. We can reformulate Descartes’ “Cogito ergo sum” from a Heideggerian perspective: I am, therefore the world is. Also, Heidegger uses the word “existence” in a technical sense to signify Dasein’s specific mode of Being.

However, we must understand that the “Being-in” in “Being-in-the-world” doesn’t mean to be in in the way that apple juice is in a bottle. “Being-in” means Being involved. Dasein is always already involved and concerned with a world. Heidegger says that Being-in-the-world is a “unitary phenomenon.” Nevertheless, we can isolate its three constitutive “elements” for the sake of analysis. These three are: (1) the worldhood of the world; (2) the who, i.e., Dasein; (3) Being-in. We have already touched on worldhood and Dasein, but let’s momentarily focus our attention on Being-in. There is much that could be said of Being-in; we’ll limit ourselves to the aspect of it that’s most relevant to the task at hand. Being-in involves disclosing the world. Dasein, as the being with a pre-theoretical understanding of Being, opens up the world in the clearing (Lichtung). To speak of Dasein standing in the clearing is to speak of Dasein’s experience or awareness of the beings revealed there in. The clearing is Dasein’s experiential “light” through which beings show themselves from themselves. Heidegger speaks of the clearing to purposely avoid any conceptual traces of representationalism that the word “consciousness” drags behind itself. Dasein’s disclosure of the world and uncovering of entities is not, normally and usually, mediated through mental representations. Heidegger says of Dasein, “Only for an entity which is existentially cleared in this way does that which is present-at-hand become accessible in the light or hidden in the dark” (Being and Time, p. 171). The insight contained in this statement was developed in much greater detail in Heidegger’s later writings as we will soon see.

Returning to the question of the meaning of “Being”, we should now understand that in Being and Time Heidegger describes three modes of being: existence (the Being of Dasein), readiness-to-hand (the Being of equipment) and presence-at-hand (the Being of substances). At this point in his career, Heidegger believed that these were the only three modes of Being. But, by the time he began working on The Origin of the Work of Art this had changed. But what about Being in general? For early Heidegger, Being was a universal, ahistorical, transcultural understanding of beings; it was the background familiarity we all have with the practices that organize our world. However, as Heidegger kept thinking about Being, he discovered that Being has a history. This means that Being is historically and culturally situated. Being is now conceived as the vague, background “principle” upon which a particular epoch understands beings as a whole. In hindsight, Heidegger’s project in Being and Time was misguided in that its presuppositions about the nature of Being in general were faulty. We are now ready to move along to discussion of truth.

2. Truth (Unconcealment)

Heidegger was always concerned with truth throughout the course of his whole career; in Being and Time, he argued that truth is best understood as an uncovering or a discovering, instead of as adaequatio, i.e. “adequacy”, or what philosophers nowadays refer to as “correspondence.” In fact, according to Heidegger, truth-as-correspondence is based on truth-as-uncovering. The correspondence theory of truth holds that truth is the correspondence or agreement of a state of affairs with either an idea or a proposition. As far as truth-as-uncovering goes, Heidegger developed this concept of truth in one of his later essays entitled On the Essence of Truth, and this is the concept of truth that is relevant to our discussion of The Origin of the Work of Art. Heidegger argues in this later essay that truth is unconcealment. Truth (unconcealment) and untruth (concealment) are two sides of the same coin — in this case, the coin being Dasein’s openness to beings. The clearing is always a clearing that conceals while unconcealing. Heidegger is basically describing what Edmund Husserl called “adumbrations”, meaning all of the possible aspects of a phenomenon — Heidegger called these hidden aspects “shadows.” This is also what Jean-Paul Sartre meant by the word “transphenomenality.” Take, for example, the simple perception of a lamp: we always and only perceive one side of the lamp at a time, we never experience/perceive the totality of the lamp’s “shadows”, i.e., possible appearances. In unconcealing an entity, we are always already concealing it, too. And, on top of that, the fact that we conceal in this manner gets concealed as well (this second concealment is what Heidegger calls “the mystery”). Unconcealment, therefore, proximally and for the most part, involves a concealing concealment (a double concealment). It is the job of philosophy (and art can do this as well) to awaken us to this double concealment. Common sense would have us believe that there’s no need to ask philosophical questions about entities because we have such a stable and exhaustive understanding of them already, however, this is really not the case. Due to the fact that in every unconcealment there’s a host of concealments, we can never say that we’ve arrived at a final knowledge of that which is unconcealed; there are always more of its “shadows” to unconceal. This also means that there’s no privileged mode of unconcealing entities — this includes science (obviously, this essay had a lot of influence on postmodern thought). In this essay Heidegger says, “The essence of truth is freedom” (Basic Writings, ‘On the Essence of Truth’, p. 123). I’ll try my best to help clarify this statement, but it’ll take some work to unpack it. Heidegger also says later on that “the essence of truth reveals itself as freedom.” It’s important to know up front that Heidegger uses the words “essence”, “truth” and “freedom” in very unconventional ways here; simply put, he gives all three of these signifiers new meanings. Let’s start by getting familiar with Heidegger’s usage of these three terms.

Essence: “Essence” doesn’t signify the defining qualities that a particular set of entities (cats, trees, cars, chairs, etc.) have in common; Heidegger defines the word like this: ““essence” is understood as the ground of the inner possibility of what is initially and generally admitted as known” (Basic Writings, ‘On the Essence of Truth’, p. 123). Heidegger’s inquiries into certain essences are similar to Immanuel Kant’s transcendental analyses in Critique of Pure Reason. Heidegger basically conceives of an essence as the condition or ground that makes an entity or process possible in the first place. So in On the Essence of Truth, Heidegger is seeking the condition, that on the basis of which, truth-as-correspondence (in this case, this is “what is initially and generally admitted as known”) is possible. In his commentary Heidegger’s Later Writings, Lee Braver says, “Here it is the traditional conception of truth as correspondence between statement and world that Heidegger accepts as given, but asks how it is possible. The essence of truth he is seeking is the enabling condition or ground for making assertions about beings and checking their accuracy” (p. 27). Heidegger goes on to argue that this condition is Dasein’s (humankind’s) openness to beings.

Truth: Heidegger’s concept of truth (alētheia — this is the Greek word for truth that Heidegger translated as “unconcealment”) is very original. Some commentators have interpreted Heidegger as rejecting the concept of truth-as-correspondence, but I believe this is a mistake. Mark Wrathall argues very convincingly that Heidegger did not reject truth-as-correspondence in his essay entitled “Heidegger and Truth as Correspondence.” However, what Heidegger was primarily concerned with was primordial truth (a truth more basic than the truth of correspondence — the former being the condition of the latter). For most of his career, Heidegger continually made a mistake that he came to realize in 1964 in his essay “The End of Philosophy and the Task of Thinking”, namely, that he had used the word “truth” ambiguously. Sometimes he used it to refer to truth-as-correspondence (correspondence, correctness, agreement or accordance between propositions and entities, i.e., propositional truth) and other times he used it to refer to his concept of unconcealment (primordial truth). In his 1966 seminar on Heraclitus, Heidegger said, “alētheia thought as alētheia has nothing to do with “truth”; rather, it means unconcealment.” Nevertheless, this distinction between truth-as-correspondence and truth-as-unconcealment is present throughout Heidegger’s career. With this in mind, we must remind ourselves to watch for his equivocations on the word “truth” — for the most part, context takes care of this problem. Heidegger does equivocate on the word “truth” in On the Essence of Truth, but a lot of the time he refers to truth-as-correspondence as “correctness”, which makes interpreting the essay much easier. Now that we’ve disambiguated the word “truth”, we must understand what Heidegger means by “unconcealment.” “Unconcealment” means the bringing-out-of-hiddenness (concealment) of Being and beings, the making manifest or disclosure of Being and beings. Here we have another distinction; the making manifest of Being is referred to by Heidegger as “ontological truth” or “primordial truth”, whereas the making manifest of beings (entities) is referred to as “ontic truth” — this is simply the ontological difference applied to truth. Of course, the terms of the distinction should really be “ontological unconcealment” and “ontic unconcealment.” Dasein (humankind) is that which brings Being and beings out of concealment by way of its open comportments, i.e., behaviors that concernfully “take notice” of beings, for example, using a vacuum cleaner, buying a gift or lighting a cigarette. Here’s the sticking point: making assertions is just another open comportment to beings, and this comportment, like all other comportments, presupposes the unconcealment of entities. Heidegger says, “The traditional assignment of truth exclusively to statements as the sole essential locus of truth falls away. Truth does not originally reside in the proposition” (Basic Writings, ‘On the Essence of Truth’, p. 122). Thus, unconcealment (ontological/ontic truth) is the essence (condition or ground) of truth-as-correspondence (propositional truth). But what then is the essence of unconcealment?

Freedom: Out of the three key words in the statement under discussion, “freedom” is definitely used in the strangest way. Heidegger doesn’t mean by it free will in the normal sense. If he did then the statement “the essence of truth is freedom” would obviously be absurd — in that, truth would be simply what we will it or choose it to be. He says, “Freedom for what is opened up in an open region lets beings be the beings they are. Freedom now reveals itself as letting beings be.” He goes on to say, “Freedom, understood as letting beings be, is the fulfillment and consummation of the essence of truth in the sense of the disclosure of beings” (Basic Writings, ‘On the Essence of Truth’, p. 125). He goes on to say, “Freedom is engagement in the disclosure of beings as such.” What Heidegger means by “freedom” is “letting beings be.” Also, what is meant by “open region” is what is referred to as “the clearing” in Being and Time. But what does Heidegger mean by “letting beings be”? Heidegger explains it like this: “The phrase required now — to let beings be — does not refer to neglect and indifference but rather the opposite. To let be is to engage oneself with beings. On the other hand, to be sure, this is not to be understood only as the mere management, preservation, tending, and planning of the beings in each case encountered or sought out. To let be — that is, to let beings be as the beings which they are — means to engage oneself with the open region and its openness into which every being comes to stand, bringing that openness, as it were, along with itself” (Basic Writings, ‘On the Essence of Truth’, p. 125). What Heidegger has in mind here is the manifestation of a being in Dasein’s open comportment (concernful involvement/everyday awareness); of course, this open comportment is conditioned by Dasein’s pre-theoretical understanding of Being. In letting beings be the beings they are, Dasein brings beings into “contact” with Being — thus, letting them be what they are. In the case of a broom, “freedom” is what happens to it when it’s “lit up” in the clearing of Dasein through an open comportment. In picking up a broom and sweeping the floor, Dasein frees the broom to be what it really is, namely, that which one uses in order to sweep the floor; Dasein “actualizes” the broom. Dasein ontologically liberates the broom. To truly understand this line of thinking, one must first be familiar with the phenomenological descriptions of equipment presented in Being and Time.

We are now in position to understand what Heidegger meant when he said, “the essence of truth is freedom.” We can reword the sentence in this way: “the condition or ground of unconcealment (and, thus, truth-as-correspondence as well, considering that unconcealment is its condition) is Dasein’s “ability” to let beings be, i.e., Dasein’s “freedom.” We are now conceptually and terminologically prepared to discuss The Origin of the Work of Art.

The Origin of the Work of Art

The Origin of the Work of Art is comprised of an introduction; three short essays: (1) “Thing and Work”, (2) “The Work and Truth”, and, (3) “Truth and Art (in truth, however, they’re best thought of as three sections due to their developmental continuity); an epilogue and an addendum. The essay is based on a series of lectures Heidegger gave in Zurich and Frankfurt during the 1930s; it was originally drafted by Heidegger between 1935 and 1937 and he eventually reworked it for publication in 1950 and again in 1960. I feel that I must inform you that in this explicative summary we’re only going to be able to discuss the introduction and the first two sections of this essay.

Heidegger begins this essay with a discussion of the word “origin.” He says, “Origin here means that from which and by which something is what it is and as it is. What something is, as it is, we call its essence. The question concerning the origin of the work of art asks about its essential source” (Basic Writings, ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’, p. 143). To put it another way, “origin” means that which ontologically conditions a being, i.e. that on the basis of which a particular being is the kind of being it is. So the “origin” of the work of art basically means the “mode of Being” of the work of art. The mode of Being of the work of art will turn out to be art itself. Heidegger makes it clear that he is seeking the ontological origin of artworks by diverting from the usual view (the ontic/causal view) which holds that the origin of a work of art is the artist. Heidegger points out that the usual view moves in a hermeneutic circle because not only is the artist the cause of the work — the work, in turn, is the cause of the artist. This is true based on the fact that “‘One is’ what one does”, which is to say that Dasein is always already a self by doing what it takes in order to be that self. In the case of a Dasein that happens to be an artist, this Dasein had to do what it takes to be an artist, which, of course, is making artworks: without works of art there would be no artists. Heidegger puts it this way, “The artist is the origin of the work. The work is the origin of the artist. Neither is without the other. Nevertheless, neither is the sole support of the other. In themselves and in their interrelations artist and work are each of them by virtue of a third thing which is prior to both, namely, that which also gives artist and work of art their names — art.” Art, as a mode of Being, makes both artist and artwork ontologically possible, so this essay turns out to be an investigation of a mode of Being unaccounted for in Being and Time.

This leads us to two questions: (1) What is the essence of art? (2) How and where are we to discover this essence? Here’s how Heidegger answered the second question: “[W]e shall attempt to discover the essence of art in the place where art undoubtedly prevails in an actual way. Art essentially unfolds in the artwork” (Basic Writings, ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’, p. 144). Heidegger continues to utilize the method he used in Being and Time, i.e., the method of phenomenology. The motto of this method was “Back to the things themselves.” Phenomenology, as developed by Heidegger’s teacher Edmund Husserl, was the study of the intentional and representational structures of consciousness as experienced from the first-person perspective. While Heidegger was deeply influenced by Husserl’s phenomenology, he also transformed it by putting an ontological spin on it (whereas Husserl’s phenomenology emphasized consciousness and intentionality, Heidegger’s phenomenology emphasized Being). Heidegger was convinced that the best way to understand an entity is to understand it in its Being, and its Being can only be discovered by looking at it, not through theorization or the analysis of concepts: “Before words, before expressions, always the phenomena first, and then the concepts!” (History of the Concept of Time, p. 248). Philosophy, for far too long, had tried to fit all beings into one category scheme, making theory more primary than phenomena themselves. Heidegger insisted that we must “let what shows itself be seen from itself, just as it shows itself from itself.” This is precisely what he intends to do with works of art.

So if we are to discover the essence of art we must discover it by phenomenologically investigating artworks, but here we arrive at yet another circle. “What art is should be inferable from the work. What the work is we can come to know only from the essence of art. Anyone can easily see that we are moving in a circle” (Basic Writings, ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’, p. 144). To investigate a work of art presupposes that we have an understanding of what art is, otherwise we couldn’t differentiate works of art from other types of beings. Ever since Plato expressed the paradox of inquiry (Meno’s paradox), philosophers have been attempting to solve it. In the dialogue Meno, Plato states the paradox straightforwardly: “[A] man cannot try to discover either what he knows or what he does not know [.] He would not seek what he knows, for since he knows it there is no need of the inquiry, nor what he does not know, for in that case he does not even know what he is to look for.” However, for Heidegger, this hermeneutic circularity isn’t a problem at all, in fact, it makes inquiry possible in the first place:

“Ordinary understanding demands that this circle be avoided because it violates logic. What art is can be gathered from a comparative examination of actual artworks. But how are we to be certain that we are indeed basing such an examination on artworks if we do not know beforehand what art is? And the essence of art can no more be arrived at by derivation from higher concepts than by a collection of characteristics of actual artworks. . . . Thus we are compelled to follow the circle. This is neither a makeshift or a defect. To enter upon this path is the strength of thought, assuming that thinking is a craft. Not only is the main step from work to art a circle like the step from art to work, but every separate step that we attempt circles in this circle.”

(Basic Writings, ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’, p. 144)

What Meno’s paradox fails to take account of is the distinction between our vague understanding of x and our theoretical understanding of x. For example, in Being and Time, Heidegger established that Dasein is the being that has a tacit, pre-theoretical understanding of Being, and this is precisely why it can pursue an explicit, theoretical understanding of Being.

Having dealt with the “problem” of circularity, Heidegger proceeds to explain that despite whatever else artworks may be, one thing is clear — they are things:

“[W]orks are as naturally present as things. The picture hangs on the wall like a rifle or a hat. A painting, e.g., the one by Van Gogh that represents a pair of peasant shoes, travels from one exhibition to another. Works are shipped like coal from the Ruhr and logs from the Black Forest. During the First World War Hölderlin’s hymns were packed in the soldier’s knapsack together with cleaning gear. Beethoven’s quartets lie in the storerooms of the publishing house like potatoes in a cellar.”

(Basic Writings, ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’, p. 145)

Works of art are things (or, at the very least, have a thingly character), and, by “things”, Heidegger means present-at-hand entities. But this seems to be a gross reduction of artworks; it’s true that they have a thingly element but aren’t they also more than just brute things? Heidegger says, “But even the much-vaunted aesthetic experience cannot get around the thingly aspect of the artwork. There is something stony in a work of architecture, wooden in a carving, colored in a painting, spoken in a linguistic work, sonorous in a musical composition.” He goes on to say, “The thingly element is so irremovably present in the artwork that we are compelled rather to say conversely that the architectural work is in stone, the carving is in wood, the painting in color, the linguistic work in speech, the musical composition in sound.” But what exactly is this thingly character of the work of art? We must keep in mind that “the artwork is something over and above the thingly element” (Basic Writings, ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’, p. 145). Heidegger then explains that this other something has long been interpreted as allegory or symbol, thus making the artwork a combination of thing and symbol. Heidegger then claims that if we’re to understand the work of art, we must first understand what a thing is. This leads to an investigation of thingness focusing, of course, on the thingness of artworks. (This is a strange move considering that Heidegger’s phenomenological method maintains that we must discover the Being of a particular being by looking at beings with that mode of Being. If we are searching for the Being of artworks, then why are we going to investigate the Being of things? This seems inconsistent with Heidegger’s method. We’ll return to this issue later on.)

Thing and Work

Heidegger starts off this section by giving examples of things. He then goes on to discuss the sorts of beings that should and should not be called “things.” Heidegger suggests that God, people and animals shouldn’t be considered things in the strict sense of the word, and that we should limit our analysis to mere things because they are the only beings that count as things in the proper sense. To establish the thingness of things, Heidegger moves into a discussion of the three predominant interpretations of thingness developed in the Western philosophical tradition. The first interpretation of thingness is the one developed by Aristotle, René Descartes and John Locke, namely, that things are substances with accidents; let us call this view “substance ontology.” The second interpretation understands things to be the unities of sensations, this is basically the view of thingness found in the empiricism of George Berkeley and David Hume, i.e., phenomenalism. Heidegger rejects both of these interpretations. Of the first he says, “it does not lay hold of the thing as it is in its own being, but makes an assault upon it.” The point is that we simply don’t experience things as substances with accidents. While this interpretation is given grammatical support by the subject-predicate schema of categorical propositions, it ultimately is an imposition on phenomena, meaning that it’s a theory we force on things in order to make sense of them in a theoretical manner. Heidegger refutes the second interpretation by once again keeping his eye on the phenomenon: “We never really first perceive a throng of sensations, e.g., tones and noises, in the appearance of things — as this thing-concept alleges; rather we hear the storm whistling in the chimney, we hear the three-motored plane, we hear the Mercedes in immediate distinction from the Volkswagen. Much closer to us than all sensations are the things themselves. We hear the door shut in the house and never hear acoustical sensations or even mere sounds. In order to hear a bare sound we have to listen away from things, divert our ear from them, i.e., listen abstractly.” Heidegger ends his discussion of the first two thing-concepts by saying, “Whereas the first interpretation keeps the thing at arm’s length from us, as it were, and sets it too far off, the second makes it press too physically upon us. In both interpretations the thing vanishes. It is therefore necessary to avoid the exaggerations of both.” The first interpretation “keeps the thing at arm’s length” in the sense that it buries the thing beneath its properties, and the second makes the thing “press too physically upon us”, which is to say that it reduces the thing to our mere perceptions of it.

The third interpretation is that of hylomorphism, which holds that the thingness of a thing is to be thought in terms of matter (hyle) and form (morphē) (this interpretation was also developed by Aristotle). Heidegger summarizes this thing-concept: “What is constant in a thing, its consistency, lies in the fact that matter stands together with a form. The thing is formed matter.” Out of the three thing-concepts, Heidegger takes the third one the most seriously. This interpretation stands out because it applies to things as well as equipment; it also allows us to answer the question concerning the thingly aspect of artworks: “The thingly element is manifestly the matter of which it consists. Matter is the substrate and field for the artist’s formative action.” The matter-form schema seems to perfectly represent the thingly character of works of art. Especially since these categories have played such an important role in aesthetics and art theory: The distinction of matter and form is the conceptual schema which is used, in the greatest variety of ways, quite generally for all art theory and aesthetics. This incontestable fact, however, proves neither that the distinction of matter and form is adequately founded, nor that it belongs originally to the domain of art and the artwork.” Here, Heidegger is urging us to keep a certain amount of mistrust towards this schema. Why? Well, for one reason: this schema is incredibly commonplace, and every entity can be squeezed into it. However, if it applies to every entity, then how can it be used to differentiate things that are works of art from other types of things? Heidegger’s analysis of this schema leads him to discover that it best applies to the usefulness of equipmental things: “As determinations of beings, accordingly, matter and form have their proper place in the essential nature of equipment.” The third interpretation, like the first two, fails in the end. If the matter-form schema is ultimately tied up with usefulness and equipmentality, then it cannot be used to explain the mere thingness of a thing, since this mere thingness only comes to our view by suspending (bracketing) the usefulness of the useful thing — seeing how this thing-concept isn’t derived from the essence of the mere thing but from the essence of equipment. If the matter-form schema only applies to useful things, then the moment we bracket a thing’s usefulness and arrive at the mere thing itself, the schema is inapplicable, thus, it cannot be used to explain the thingness of the mere thing. Perhaps we could use this thing-concept if mere things and works of art were subspecies of equipment, but they’re not. Nevertheless, Heidegger suggests that we should investigate the equipmentality (Being) of equipment because it might contain a clue that will guide us to an understanding of the thingly character of the thing and the workly character of the artwork. (This might seem superfluous considering Heidegger already undertook this task in Being and Time.)

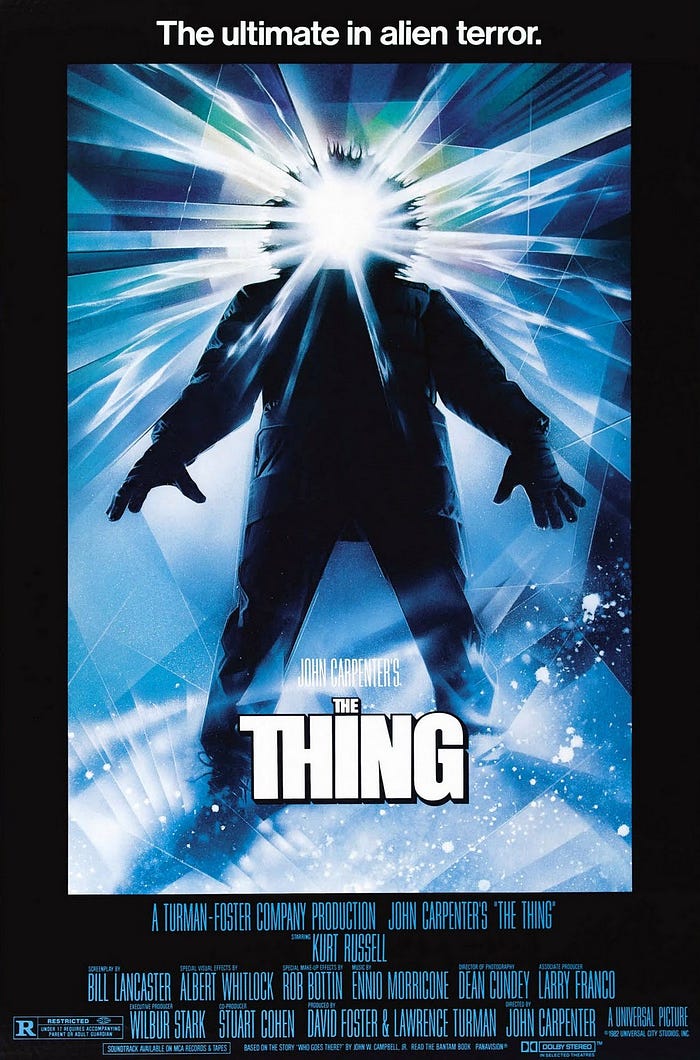

But how should we go about discovering the equipmentality of equipment? Heidegger suggests we examine a pair of peasant shoes and that a pictorial representation of them will suffice — He chooses one of Van Gogh’s paintings of peasant shoes as his example. We are all familiar with shoes, know what they’re made out of, and understand their purpose. But in order to understand their usefulness as such we must see them in use. Heidegger offers a description: “The peasant woman wears her shoes in the field. Only here are they what they are. They are all the more genuinely so, the less the peasant woman thinks about the shoes while she is at work, or looks at them at all, or is even aware of them. She stands and walks in them. That is how shoes actually serve. It is in this process of the use of equipment that we must actually encounter the character of equipment.” This description lines up nicely with the description of equipment in Being and Time. Once again, Heidegger points out that equipment, when fully functional, withdraws. But, all of a sudden, Heidegger becomes skeptical about the possibility of this sort of inquiry: “As long as we only imagine a pair of shoes in general, or simply look at the empty, unused shoes as they merely stand there in the picture, we shall never discover what the equipmental being of the equipment in truth is. From Van Gogh’s painting we cannot even tell where these shoes stand. There is nothing surrounding this pair of peasant shoes in or to which they might belong — only an undefined space. There are not even clods of soil from the field or the field-path sticking to them, which would at least hint at their use. A pair of peasant shoes and nothing more. And yet.” The “and yet” signifies a glimmer of hope. Heidegger follows up with a poetic description: “From the dark opening of the worn insides of the shoes the toilsome tread of the worker stares forth. In the stiffly rugged heaviness of the shoes there is the accumulated tenacity of her slow trudge through the far-spreading and ever-uniform furrows of the field swept by a raw wind. On the leather lie the dampness and richness of the soil. Under the soles stretches the loneliness of the field-path as evening falls. In the shoes vibrates the silent call of the earth, its quiet gift of the ripening grain and its unexplained self-refusal in the fallow desolation of the wintry field. This equipment is pervaded by uncomplaining worry as to the certainty of bread, the wordless joy of having once more withstood want, the trembling before the impending childbed and shivering at the surrounding menace of death. This equipment belongs to the earth, and it is protected in the world of the peasant woman. From out of this protected belonging the equipment itself rises to its resting-within-itself.” Van Gogh’s painting reveals both the Being of equipment and the peasant women’s world to us (Heidegger also mentions earth for the first time in this passage; this “concept will prove to be very important to the Being of the work of art). Heidegger now claims that the equipmental Being of equipment has shown itself to be reliability.

“The equipmental being of the equipment consists indeed in its usefulness. But this usefulness itself rests in the abundance of an essential Being of the equipment. We call it reliability. By virtue of this reliability the peasant woman is made privy to the silent call of the earth; by virtue of the reliability of the equipment she is sure of her world. World and earth exist for her, and for those who are with her in her mode of being, only thus — in the equipment. We say “only” and therewith fall into error; for the reliability of the equipment first gives to the simple world its security and assures to the earth the freedom of its steady thrust. . . . Only in this reliability do we discern what equipment in truth is.”

(Basic Writings, ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’, pp. 160–1)

While the examination of Van Gogh’s painting has revealed the equipmentality of equipment, it has not shed any light on the thingness of the thing or the artness of the artwork. Or have we unknowingly learned something about the artness of the artwork? In fact, we most certainly have. “The artwork lets us know what shoes are in truth. . . . [T]he equipmentality of equipment first expressly comes to the fore through the work and only in the work” (Basic Writings, ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’, p. 161). Works of art are beings that do something very special, ontologically speaking — they reveal beings as they truly are in their mode of Being. The work of art is the site of the truth (unconcealment) of beings. The Being of beings is made to stand out (made explicit) in unconcealment in the artwork. If we think back to our discussion of On the Essence of Truth we’ll remember that while the Being of beings is unconcealed in Dasein’s clearing, this unconcealment itself normally involves a double concealment. On top of that, Dasein has a tendency (what Heidegger called “fallenness”) to lose itself in gossip and in its present concern with beings, thereby forgetting Being and unconcealment. Artworks can break the chains of the forgetfulness of Being by bringing us to the experience of it. Of Being, truth and works of art, Heidegger states, “What happens here? What is at work in the work? Van Gogh’s painting is the disclosure of what the equipment, the pair of peasant shoes, is in truth. This being emerges into the unconcealment of its Being. The Greeks called the unconcealment of beings alētheia. We say “truth” and think little enough in using this word. If there occurs in the work a disclosure of a particular being, disclosing what and how it is, then there is here an occurring, a happening of truth at work. In the work of art the truth of beings has set itself to work. “To set” means here “to bring to stand.” Some particular being, a pair of peasant shoes, comes in the work to stand in the light of its Being. The Being of beings comes into the steadiness of its shining.” This means, very counterintuitively I might add, that works of art are essentially “about” truth and Being — not beauty. Heidegger has finally arrived at the essence of art: “The essence of art would then be this: the truth of beings setting itself to work.” Heidegger himself realized that this is a strange position: “But until now art presumably has had to do with the beautiful and beauty, and not with truth. The arts that produce such works are called the fine arts, in contrast with the applied or industrial arts that manufacture equipment. In fine art the art itself is not beautiful, but is called so because it produces the beautiful. Truth, in contrast, belongs to logic. Beauty, however, is reserved for aesthetics.”

In the closing paragraphs of this sections, Heidegger (1) clarifies that by “truth” he doesn’t mean adaequatio (correspondence), (2) rejects the view that art is essentially representational or mimetic, and, (3) shows that the search for the thingly aspect of the work of art rested on a category mistake. He then states that two points have become clear to us: “First, the dominant thing-concepts are inadequate as means of grasping the thingly aspect of the work. Second, what we tried to treat as the most immediate actuality of the work, its thingly substructure, does not belong to the work in that way at all.” Heidegger then acknowledges that the method of inquiry utilized throughout this section was faulty, since we were trying to arrive at the Being of the work of art by investigating things and equipment — this is simply the wrong approach from the phenomenological perspective. “What matters is a first opening of our vision to the fact that what is workly in the work, equipmental in equipment, and thingly in the thing comes closer to us only when we think the Being of beings.” So if Heidegger knew better, then why did he take us on so many unnecessary detours? I believe he did this because he wanted us to think along with him, and not merely read the final results of his own thinking. Heidegger closes out this section by reiterating the most important discovery thus far: “The artwork opens up in its own way the Being of beings. This opening up, i.e., this revealing, i.e., the truth of beings, happens in the work. In the artwork, the truth of beings has set itself to work. Art is truth setting itself to work.” We can now turn our attention to the second section of the essay, and, let me just say up front that this is where things really begin to get interesting.

The Work and Truth

Given the title of this section, we can infer that Heidegger is going to continue to investigate the relation between works of art and the essence of art (the highlighting of the unconcealment of unconcealment). In the first section, it was established that the essence of art is the happening of truth, but the question remains: how does truth happen in a work of art? We begin section two with an ontological announcement: “The origin of the work of art is art.” But Heidegger immediately returns to inquiring into the nature of art. Heidegger then makes another counterintuitive claim, namely, that the artist is relatively unimportant when compared to the importance of the work itself: “It is precisely in great art — and only such art is under consideration here — that the artist remains inconsequential as compared with the work, almost like a passageway that destroys itself in the creative process for the work to emerge.” (We must note that Heidegger specifies that he is only taking account of great works of art in this essay.) The artwork remains an artwork outside of the relations it has to the artist that created it, thus, the work-Being (art-Being) of the work cannot be explained in terms of these relations. Nor can the art industry shed any light on the work-Being of the work, since it is primarily concerned with works-as-objects, i.e. things to be stored away, preserved, displayed, sold, etc. The art industry only gets at the thing-Being or the object-Being of the work.

Heidegger then reveals something quite profound about artworks and the relations they have to their respective worlds: “The Aegina sculptures in the Munich collection, Sophocles’ Antigone in the best critical edition, are, as the works they are, torn out of their own native sphere. However high their quality and power of impression, however good their state of preservation, however certain their interpretation, placing them in a collection has withdrawn them from their own world. But even when we make an effort to cancel or avoid such displacement of the works — when, for instance, we visit the temple in Paestum at its own site or the Bamberg cathedral on its own square — the work that stands there has perished.” For Heidegger, the key relation belonging to an artwork is the relation it has (or had) with the world in which it was truly “alive.” A work of art is a “living” work of art if and only if its world is alive. This means that artworks and worlds are deeply interconnected. Throughout his early work, Heidegger often spoke of deworlding; what he meant by this is viewing Dasein or equipment as purely present-at-hand entities outside of their worldly context, for instance, viewing a chair outside of the worldly relations and references that make it most basically what it is, i.e., a piece of equipment. Heidegger is now presenting us with an example of deworlding the work of art. He continues on this train of thought: “World-withdrawal and world-decay can never be undone. The works are no longer the works they were. It is they themselves, to be sure, that we encounter there, but they themselves are gone by. As bygone works they stand over against us in the realm of tradition and conservation. Henceforth they remain merely such objects.” The best way of putting this is to say that “bygone” or “dead” artworks no longer do what they once did. But we are still not yet clear on what exactly it is that “living” works of art do.”

To get clear about this, Heidegger decides to examine another artwork, and he goes out of his way to make sure that it’s completely a non-representational work: a Greek temple:

“A building, a Greek temple, portrays nothing. It simply stands there in the middle of the rock-cleft valley. The building encloses the figure of the god, and in this concealment lets it stand out into the holy precinct through the one portico. By means of the temple, the god is present in the temple. This presence of the god is itself an extension and delimitation of the precinct as a holy precinct. The temple and its precinct, however, do not fade away into the indefinite. It is the temple work that first fits together and at the same time gathers around itself the unity of those paths and relations in which birth and death, disaster and blessing, victory and disgrace, endurance and decline acquire the shape of destiny for human being. The all-governing expanse of this open relational context is the world of this historical people. Only from and in this expanse does the nation first return to itself for the fulfillment of its vocation.”

(Basic Writings, ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’, p. 167)

What the work of art essentially does is set up a world: “To be a work means to set up a world.” For Heidegger, “setting up” means “erecting in the sense of dedication and praise.” Whereas Van Gogh’s painting merely disclosed a world to us (a world to which it doesn’t actually belong), the world of the peasant woman, the Greek temple, on the other hand, actually brought about a world. “The temple, in its standing there, first gives to things their look and to men their outlook on themselves.” The Greek temple set up a world that organized and stabilized the lives of the Greeks; it was that by which they made sense out of their existence. Medieval cathedrals did the exact same thing for Christians and the great mosques did the same for Muslims. Again, a world is the significant, contextual network of references through which a particular Dasein can take the stand on its Being that it does (be the specific person that it is), as well as have the style of Being that it has. Heidegger offers us a definition of “world”: The world is the self-opening openness of the broad paths of the simple and essential decisions in the destiny of a historical people.” He also says, “The world worlds, and is more fully in being than the tangible and perceptible realm in which we believe ourselves to be at home. World is never an object that stands before us and can be seen. World is the ever-nonobjective to which we are subject as long as the paths of birth and death, blessing and curse keep us transported into Being.” “The world worlds” refers the the world’s essential activity. The world as a world is always essentially doing something. Heidegger uses this sort of language in the attempt to direct our attention to a phenomenon without distorting it; another example of this is found in his essay What Is Metaphysics where he famously claims that “[t]he Nothing itself nothings” (alternatively translated as “the Nothing nothings”). All Heidegger means by “the world worlds” is that the world orients, situates, guides and directs our lives in particular ways. The temple established an epochal understanding of Being on the basis of which the Greeks meaningfully understood the beings they encountered and the events in their lives, thereby, giving them as a people a history or a destiny.

But the setting up of a world is just the first essential feature of the Being of the work of art. The second essential feature of the Being a work of art is the setting forth of the earth. Heidegger shows that whereas the materiality of equipment is both used and used up in the equipment, the materiality of the work of art is only used. By “used” he means that material is employed in the making of a piece of equipment or an artwork, and by “used up” he means withdraws out of notice, however, it withdraws in two senses: (1) it withdraws into the assignment or purpose of a piece of equipment by being “fused”to it, and, (2) it withdraws into Dasein’s skillful coping with a piece of equipment. So to be clear, the materiality of equipment is used up (withdraws) whenever the equipment is functioning, by contrast, whenever the artwork is “functioning” its materiality announces itself:

“In fabricating equipment — e.g., an ax — stone is used, and used up. It disappears into usefulness. The material is all the better and more suitable the less it resists vanishing in the equipmental being of the equipment. By contrast the temple-work, in setting up a world, does not cause the material to disappear, but rather causes it to come forth for the very first time and to come into the open region of the work’s world. The rock comes to bear and rest and so first becomes rock; metals come to glitter and shimmer, colors to glow, tones to sing, the word to say. All this comes forth as the work sets itself back into the massiveness and heaviness of stone, into the firmness and pliancy of wood, into the hardness and luster of metal, into the brightening and darkening of color, into the clang of tone, and into the naming power of word.”

(Basic Writings, ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’, p. 171)

Some commentators hold that the concept of earth has nothing whatsoever to do with the materiality of the work of art, but I find this interpretation difficult to accept (however, I must admit that there is some textual support for this position). I believe that earth designates, at least to some degree, the materiality of the work: “[T]he temple-work, in setting up a world, does not cause the material to disappear, but rather causes it to come forth for the very first time and to come into the open region of the work’s world… That into which the work sets itself back and which it causes to come forth in this setting back of itself we call the earth.” Heidegger defines “earth” like this: “The earth is the spontaneous forthcoming of that which is continually self-secluding and to that extent sheltering and concealing.” The concept of earth is, in my opinion, the most important contribution Heidegger makes in this essay. World and earth are opposed to one another, and, yet, depend on each other. World is best associated with unconcealment, the clearing and intelligibility, and earth is best described in terms of concealment, hiddenness and unintelligibility. Earth seems similar to what Jacques Lacan referred to as “the Real”. For Lacan, the order of the Real, as opposed to the order of the the Symbolic, is that which evades all symbolic representation while pushing back against it. The Real is located beyond language and conceptual understanding and, yet, always present in some sense: Lacan said, “For the real, whatever upheaval we subject it to, is always and in every case in its place; it carries its place stuck to the sole of its shoe, there being nothing that can exile it from it.” Here’s an alternate translation of this passage: “The Real is something you find always at the same place. However you mess about, it is always in the same place, you bring it with you, stuck to the sole of your shoe without any means of exiling it” (Écrits, ‘Seminar on ‘The Purloined Letter’’, p. 17). Earth, like the Real, resists our attempts to assimilate it into our world. Heidegger says, “Earth thus shatters every attempt to penetrate it. . . . The earth appears openly cleared as itself only when it is perceived and preserved as that which is essentially undisclosable, that which shrinks from every disclosure and constantly keeps itself closed up” (Basic Writings, ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’, p. 172). Earth is that which alludes being made intelligible or semiotically captured by systems of meaning. We can think of the relation between world and earth as a contestation between light and darkness (But we must keep in mind that world and earth are essential to each other). Just as unconcealment and concealment are built into the clearing of Dasein, so, too, are intelligibility and mystery (obscurity) built into the work of art (the being which opens and holds open a particular clearing).

Here we can see the influence of the German philosophical tradition on Heidegger. The German philosophers in general always left space for the mysterious or the unintelligible. Take Kant, for instance, with his phenomena-noumena distinction (noumena being unintelligible); or take Nietzsche with his distinction between the Apollonian and the Dionysian (of course, the latter is opposed to the clarity and rationality of the former). This line of thinking has deep roots in German philosophy.

In the work of art, earthly elements (stones, woods, pigments, etc.) are consecrated and transfigured into something radiant and mysterious which the human intellect cannot make completely comprehensible and assimilable. This is easy enough to see phenomenologically: when looking at a work of art the meaning of it oftentimes alludes us; we find ourselves wrestling with the work in order to make it fully intelligible, which, of course, never actually happens with a great work of art. While the world speaks out to us in the work, earth remains enigmatically silent. Earth is a “self-secluding mystery” that gets set forth (herstellan — literally, ‘places here, towards us’) in the work. Earth is really responsible for the presencing of a world in the work of art, i.e., it’s the element that catches the eye. But how does it do this? In Being and Time it was shown that the ontological “gestalt shift” between transparently using equipment in its withdrawnness and viewing it as a present-at-hand thing (object) with certain properties normally occurs in the case of a breakdown, which is to say when a piece of equipment either is missing or brakes. The breakdown causes Dasein to stand back from the equipment instead of being involved with it transparently. We cease to be circumspectively concerned with our environment — we cease to be lost in it, i.e., we cease to lose ourselves in it — and, instead, take up an objective view towards it. Malfunction is the pivot from transparency to opacity, however, once the tool is either found or fixed, the equipment can once again withdraw into use. Of course, if a piece of equipment brakes and we know immediately how to fix it, then there’s really no opacity or confusion in this breakdown, however, this usually isn’t the case. Normally, we’re confused for a period of time as to how to get the tool functioning again (the same goes in the case of a missing tool: if we immediately remember where it’s at, then we go back into the mode of circumspective involvement, locate the tool, and then carry on with whatever we were doing). Earth does something similar to a breakdown — but it’s not the exact same thing. Earth, like a breakdown, is opaque, confusing and perplexing, however, unlike a breakdown, we cannot “fix” earth so as to make it transparent. Earth is different from a breakdown in another sense: it itself resists “fixing” (intelligibility or understanding). Yet earth is that in the work of art that makes the work stand out or become present to us. The world is usually invisible or transparent to us in our everyday activities, and a breakdown is usually a breakdown in our own little world (not the world at large), so how is the world to become visible? It becomes visible through the opacity of earth in an artwork. In a great work of art there’s always a strife between transparent intelligibility (world) and opaque unintelligibility (earth). Earth is that opaque and perplexing element, like a breakdown, that makes the world present itself to us, but, unlike a breakdown, it’s “unfixable” — it makes us take notice of the work of art precisely because it lacks the transparent intelligibility which characterizes our everyday world. However, it is only through the transparency of the world that earth can strike us as unintelligible, perplexing and mysterious. Leonardo de Vinci’s Mona Lisa, Bob Dylan’s “Desolation Row”, David Lynch’s Blue Velvet and Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey are all good examples of the struggle between world and earth. These works are never semiotically exhausted or depleted, i.e., finally made totally intelligible.

Heidegger moves on to a discussion of strife. He says, “The opposition of world and earth is strife.” World and earth are mutually constitutive of one another:

“World and earth are essentially different from one another and yet are never separated. The world grounds itself on the earth, and earth juts through world. Yet the relation between world and each does not wither away into the empty unity of opposites unconcerned with one another. The world, in resting upon the earth, strives to surmount it. As self-opening it cannot endure anything closed. The earth, however, as sheltering and concealing, tends always to draw the world into itself and keep it there.”

(Basic Writings, ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’, p. 174)

Heidegger goes on to say that in strife world and earth “raise each other into the self-assertion of their essential natures.” The happening of truth in the work of art and the Being of the work of art is essentially the the instigation of the strife between world and earth: “The work-being of the work consists in the instigation of the strife between world and earth” (Basic Writings, ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’, p. 175). World and earth are always already in strife but what a great work of art uniquely does is intensify and showcase this strife, i.e., it “instigates” it while establishing it. This strife is the motor of the happening of truth. Through strife, unconcealment as unconcealment highlights itself in the clearing of Dasein. The strife which unconceals unconcealment is like the “motion” of a Gestalt shift — unconcealment occurs in the back-and-forth motion (strife) of world and earth. The great work of art is the being that establishes and sustains an epochal understanding of Being. The work of art is essentially the truth event of the Being of beings. The work of art is a happening-repose or a reposed-happening in the sense that the work simultaneously opens up a world (happening) and keeps that world open across of period time in a stable form (repose). The work is, thus, a motion-in-rest or a rest-in-motion. There’s definitely a trace of per-Socratic thought, especially Heraclitus’ concept of ἔρις (eris, “strife”), in Heidegger’s concept of strife.

After his short discussion of strife Heidegger moves on to an analysis of the concept of truth (truth-as-unconcealment). Heidegger basically reiterates with brevity what he already said about truth in On the Essence of Truth, so there’s really no need to discuss this analysis in detail since we’re already familiar with what he had to say on the subject. However, Heidegger does make a good point here, namely, that what is most common in our existences (the unconcealment of beings in the clearing) is, in fact, what’s truly incredible: “At bottom, the ordinary is not ordinary; it is extraordinary” (Basic Writings, ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’, p. 179).

Heidegger ends this section by saying that in this analysis of the relation between artworks and truth that we have failed to take into account of an important aspect of works of art, namely, the fact that they are created. He says, “If there is anything that distinguishes the work as work, it is that the work has been created.” If truth and createdness are essentially related to works of art, then we must examine their relation to one another.

Conclusion

We have arrived at the conclusion of our discussion of Heidegger’s The Origin of the Work of Art. I must confess that we have only scratched the surface of this essay. But what we have learned about art is most certainly eyeopening and incredibly original. Just think about it, we have discovered that art can be thought of in terms of Being, truth, world, earth and strife — who could have ever guessed that? Heidegger was a philosopher who always uncovered new insights throughout the course of his thinking and nowhere is that more explicit than in this essay. What I personally find to be the most important discoveries in this essay are (1) that the two essential features of a great artwork are the setting up of a world and the setting forth of earth, and, (2) that an epochal understanding of Being and a particular world are opened and held opened in Dasein’s clearing by a specific being, i.e., a work of art. Anthropology and sociology both have shown the deep connection between human beings and works of art, but what Heidegger has shown is the ontological connection between the two. Insofar as the work of art plays an essential role in the clearing it has a primordial relation to Dasein.

Works Cited

Braver, Lee, Heidegger’s Later Writings. New York: Continuum International Publishing Group. 2009.

Descartes, René, The Philosophical Writings of René Descartes: Volume I. Cambridge: Cambridge University Pres. 1984.

Heidegger, Martin, Being and Time. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco. 1962.

Heidegger, Martin, Basic Writings. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco. 1993.

Heidegger, Martin, History of the Concept of Time. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. 1985.

Heidegger, Martin, The Basic Problems of Phenomenology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. 1982.

Heidegger, Martin, Heraclitus Seminar. Evanston, IL.: Northwestern University Press. 1993.

Lacan, Jacques, ‘Seminar on The Purloined Letter’, in Écrits, New York